MODERATOR:

Mary Warner

American Pharmacists Association

Washington, DC

PRESENTERS:

Alethea Gerding

American College of Prosthodontists

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Barbara Gastel

Texas A&M University

College Station, Texas

Liz Haberkorn

American Pharmacists Association

Washington, DC

REPORTER:

Judy Connors

Owner, Do It Write Editorial, LLC

Thornton, Pennsylvania

Being in the midst of a research project I hope to turn into an article and/or poster, I found this presentation to be comprehensive, concise, and extremely helpful for a first-time poster presenter. Moderator Mary Warner of the American Pharmacists Association opened the session by reminding the audience that the essence of scientific discovery is in research and the sharing and implementation of those findings; conferences like CSE and International Society of Managing and Technical Editors (ISMTE) where articles and posters are abundant is one way of information sharing.

Remembering that a poster is a visual art form and, specifically in the scientific publishing arena, a visual abstract of sorts, will inform the main components of your poster so that it is easily readable, quickly understood, and attracts attention. The three presenters discussed different aspects of poster/article presentation and, by the conclusion of the session, attendees were well equipped to prepare either.

Alethea Gerding of the Journal of Prosthodontics opened the discussion with brainstorming ideas for a poster topic: Do you have an innovative solution to a common problem? Is there an uncommon issue you have dealt with and, if so, how was it resolved and what did you learn along the way? Are there any existing tools that can be applied to a new problem?

Once the poster topic has been decided upon, there are five considerations for developing your data:

- Describe the problem you are solving.

- Provide detailed step-by-step actions you took; screen shots work well as visuals.

- Share failures and successes, e.g., what worked and what did not.

- Analyze your results. What did you discover, solve, resolve?

- Ensure your project and subject are applicable across the board to other journals.

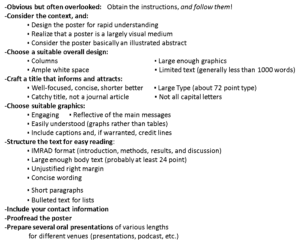

Building on Gerding’s excellent opener, Barbara Gastel, Professor of Integrative Biosciences and Medical Humanities at Texas A&M University, offered detailed guidelines and resources for turning research into either a poster or article. The first step, which is obvious but often overlooked is to obtain the Author Instructions or Guidelines and follow them! This will give you a much better chance of an acceptance for your article or poster than if the publication and/or meeting team needs to go back and forth with you on formatting and reporting requirements. See the Figure for other considerations for the design of your poster and its content.

Be sure to include your contact information (full name, degrees, affiliations, email and best phone contact number) so that you are easily reachable for inquiries. Doing a poster without these details is like purchasing an ad without your phone number!

Also important is considering “spinning” your content into different formats: a poster can then become a PowerPoint presentation, the PowerPoint can become an article, an article turns into a blog or a book chapter, etc. This takes a little while but it is a good investment and will save you research time down the road when your content is picked up for another use and your memory may not be as detailed as you would like when it comes to the specifics of your poster or presentation.

Many of the same components are critical when writing a journal article and Gastel advises to identify your first-choice journal early on so you can customize your writing style and formatting to their guidelines. Once again, obtaining and following the guidelines offered to authors for that publication are seminal to your article preparation as is familiarizing yourself with articles previously published in past issues of the journal. This not only enables you easily to see the formatting but also gives you the sense of the writing voice the journal is accustomed to. More on voice later.

The usual structure for journal articles is IMRAD style:

Introduction: What are the questions?

Methods: How did you try to answer them?

Results: What did you find?

Discussion: What does it mean?

When writing, draft sections in whatever order makes most sense to you and revise, revise, revise. Then, get feedback and revise more. Remember, peer reviewers and journal editors are your allies—they want good, solid science to publish so give it to them.

The final presenter, Liz Haberkorn, discussed writing with style and finding your research voice. Good writing is concise, clear, comprehensive, and can also be consistent and creative. Best practices include

- Avoiding clichés: You know what you want to say; use YOUR words to say it.

- Start strong: A great intro paragraph pulls in readers.

- Emphasize your main points.

- Organize your paper so it flows sensibly, this is as important in short as in long articles.

- Take risks with your writing style but never compromise your credibility for creativity.

- Ending stronger: Your intro pulls the readers in; your outro makes them think and will help you make an impression.

Resources are central to preparing a poster or journal article and the presenters provided a list of recommended ones for the audience.

Article Writing Sources:

- How to Write, Publish, and Present in the Health Sciences by Thomas A. Lang (American College of Physicians, 2009)

- How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, 8th edition, by Barbara Gastel and Robert A. Day (Greenwood Press, 2016)

- “Preparing the Four Main Parts of a Scientific Paper: Concise Advice” by Barbara Gastel (http://www.authoraid.info/en/resources/details/1322/)

- Selected other items in the AuthorAID resource library (http://www.authoraid.info/en/resources/)

Poster Sources:

- Designing Conference Posters (https://colinpurrington.com/tips/poster-design)

- “I Have the Abstract: How Do I Make It into a Poster?” by Michelle E. Stofa (https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.amwa.org/resource/resmgr/Conference/2017/SessionRoundtableHandouts/AbstractToPoster.pdf)

- “Creating Effective Poster Presentations: The Editor’s Role” by Devora Mitrany (Science Editor 28(4), 2005; https://www.councilscienceeditors.org/wp-content/uploads/v28n4p114-116.pdf)