Abstract

Background: In recent years, many journal editorial departments have begun to employ freelance editors rather than an exclusively in-house team. Although a freelance editing model offers greater editor availability and subject-matter expertise, it necessitates better quality control. We hypothesize that although a freelance model is best equipped to offer subject-matter expertise, a uniformly trained, centralized team of reviewers can help to standardize editorial quality and ensure consistency in style. To test our hypothesis, we assessed the value that an in-house reviewing team can add to a freelance editing model.

Methods: The quality of 50 academic research papers in medicine and life sciences was assessed by a panel of external editors in a blinded manner. Each paper had been edited by a freelancer and later reviewed by an in-house editor. All inhouse editors were uniformly trained in the mechanics of copyediting. The edited and reviewed versions of each paper were independently rated on clarity, language, and presentation with a four-point scale (poor = 1, excellent = 4). The results were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test (significance at P < 0.05).

Results: The mean [SD] quality score of the reviewed versions was significantly higher than that of the edited versions (P < 0.01). The improvement in score was most significant with regard to presentation (P < 0.01), followed by language (P = 0.01). With respect to clarity, although the reviewed versions scored higher than the edited versions, the difference was not significant (P = 0.06).

Conclusions: The results support our hypothesis that a freelance model can reliably offer subject-matter expertise, whereas a well-trained in-house reviewing workforce can help to implement control over language quality and presentation-related aspects of academic copy-editing. Future studies could explore technology-based or training-based methods to enhance the output of this freelancer-reviewer model.

Keywords: editing model, editorial quality, reviewing, outsourcing, in-house team

Background

In recent years, the research output of such non–English-speaking areas as Brazil, China, and the Middle East has been rapidly increasing.1 China’s contribution to the world’s aggregate scientific output, in terms of publications, more than doubled from 2002 to 2008 and continues to grow.2 However, researchers in those areas may have difficulty in writing papers in high quality English that meets international publishing standards. Despite increasing research initiatives in non–English-speaking countries, the rate of publication of papers in international journals remains low, possibly because the language quality does not meet the expected standards.3

To address the issue of poor language quality in some of the submissions coming from non–English-speaking countries, journal editors and publishers are increasingly recommending that authors who are not native speakers of English use professional editing services. Concurrently, researchers and scientists worldwide are increasingly availing themselves of manuscript-editing services with a view to polishing their papers before submission or resolving problems that have emerged during peer review.4

Against that backdrop, in the face of the global recession and the increasing volumes of research papers that require language editing, many journal editorial departments and publishing houses have begun to use a freelance editing model as opposed to an exclusively in-house model.5,6 Outsourcing editorial work is a time- and cost-effective strategy that offers greater subject-matter expertise in a wide array of disciplines and functionality across time zones but it also necessitates better quality control to ensure consistency in the application of editorial styles.5

More than 35 years ago, Boomhower7 proposed that producing a high-quality manuscript requires the combined skills of a literary editor who focuses on the mechanics of language and writing and a technical editor who looks into the manuscript content and ensures its suitability for the target reader. To the best of our knowledge, no study has explored that theory in line with the changing landscape of the publication industry. In this study, we hypothesize that although a freelance model is best equipped to offer subjectmatter expertise, a uniformly trained, centralized in-house team of reviewers can help to standardize editorial quality and ensure consistency in style. To test our hypothesis, we aimed to assess the value that a trained in-house reviewer can offer when working in conjunction with a freelance editor.

Methods

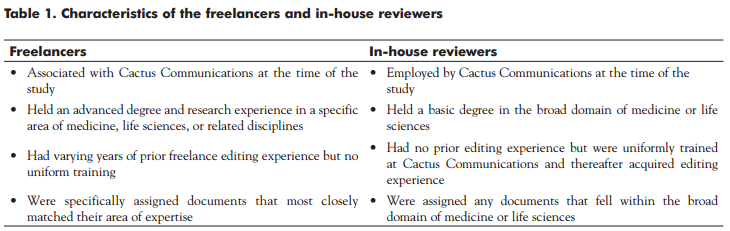

We retrospectively sampled 50 academic papers in the broad fields of medicine and life sciences. For inclusion, the manuscripts had to be research papers intended for journal publication, 1000–4000 words long, and written by Asian authors. Those inclusion criteria were enforced to ensure that all samples had a similar writing style and were within the generally accepted size range of medical and life-science research papers. All manuscripts had a uniformly poor quality of original writing as assessed subjectively by us. All manuscripts had been edited by a freelance editor (hereafter, freelancer) and reviewed by an in-house editor (hereafter, in-house reviewer). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the freelancers and in-house reviewers.

The freelancers were associated with Cactus Communications—a company that offers English-language editing services under the brand Editage and is based in Mumbai, India—at the time of the study. They were recruited as subject specialists who held advanced degrees and had research experience in specific fields of medicine, life sciences, or related disciplines. They had various numbers of years of experience as freelance academic editors but were not uniformly trained. During allocation, each manuscript was screened for its technical content and assigned to an editor who was most familiar with the topic of research.

The in-house reviewers, employed by Cactus Communications at the time of this study, held a basic degree in the broad domain of medicine or life sciences. When recruited into Cactus Communications, they had no editing experience but had an aptitude for language editing as assessed by screening tests. They were uniformly trained at Cactus Communications as described elsewhere.8 The training involved a 1-month program wherein they were taught all aspects of academic editing. They were oriented to common errors in grammar, punctuation, and sentence construction that authors who are not native speakers of English tend to make and to subject-matter conventions and writing styles. The program adopted a holistic approach, using a combination of online modules, instructor-guided discussions, and editing assignments. On successful completion of the program, the trainees’ work was reviewed by senior editors until they were deemed competent to edit independently and later to review the work of other editors. By the time of our study, the in-house reviewers had thus acquired various numbers of years of editing experience. In our study, they were assigned any documents that fell within the broad domain of medicine or life sciences.

The quality of the pre-review (hereafter, edited) and post-review (reviewed) versions of the sampled manuscripts was assessed independently by an external panel. The assessing panel comprised freelance editors who were native speakers of English; held master’s degrees or doctorates in medicine, life sciences, communication, or related fields; had at least 3 years of experience in academic editing for journal publications; and had published in Science Citation Index–indexed journals or had served as editors or peer reviewers with journals or other publications.

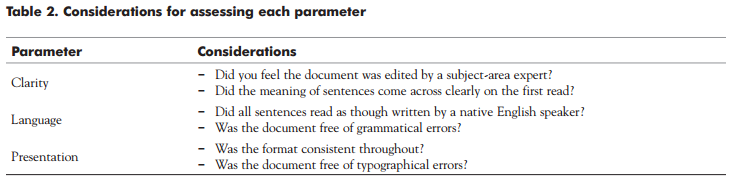

The edited and reviewed versions of each manuscript were independently assessed for clarity, language, and presentation. Clarity was defined in terms of how well the technical content was presented and how easily it would be understood by the target reader; language, in terms of grammatical accuracy and the quality of writing; and presentation, in terms of attention to detail and consistency in style (Table 2). Each version was rated on a qualitative four-point scale of poor, average, good, and excellent (Fig. 1). A single assessor rated both versions of each manuscript, and the assessor was blinded to which version was being assessed. The ratings were translated into scores (poor = 1, excellent = 4) in such a way that the maximum score for any given version was 12. The mean scores of the edited and reviewed versions were compared by using a one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, with SPSS version 16 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Next, we assessed and compared the number of edited and reviewed versions that received a poor or excellent rating. A poor rating for a given manuscript version was defined as a score of 1 for any of the three parameters (clarity, language, or presentation) or an overall score of ≤6, whereas an excellent rating was defined as a score of 4 for any parameter or ≥10 overall. Scores of 6 and 10 were considered as threshold values because an overall score of ≤6 would imply that the given manuscript version generally received a poor to average rating by the assessor on individual parameters and an overall score of ≥10 would imply that the given version was largely rated excellent or good on individual parameters.

Results

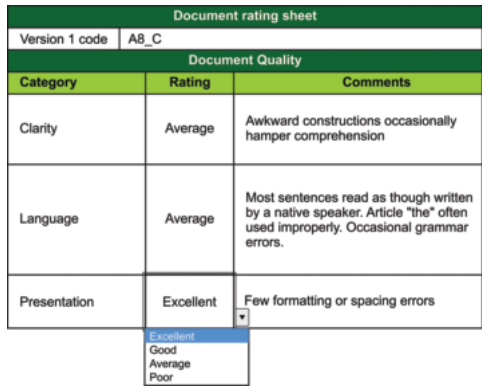

The mean [SD] quality score of the reviewed versions was significantly higher than that of the edited versions (P < 0.01), and the reviewed versions typically attained scores within a higher range (Fig. 2-A). The improvement in score was most significant with regard to presentation (mean [SD] score of edited versus reviewed versions, 2.42 [0.88] vs 3.18 [0.72]; P < 0.01), followed by language (2.44 [0.81] vs 2.92 [0.75]; P = 0.01). Although the reviewed versions scored higher than the edited versions with respect to clarity, the difference did not attain significance (2.90 [0.79] vs 3.14 [0.83]; P = 0.06; Fig. 2-B). It is consistent with that finding that only two of 50 edited versions received a poor rating (score = 1) for clarity.

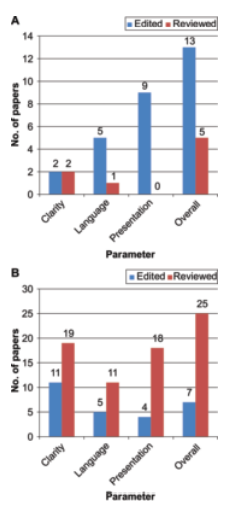

In addition, we found that for each parameter the reviewed versions generally received poor ratings less frequently (Fig. 3-A) and excellent ratings more frequently (Fig. 3-B) than the edited versions.

Discussion

Increasing global expenditure on research and development initiatives has resulted in a corresponding surge in scientific output in terms of publications. In particular, China and other Asian countries are expected to continue to contribute substantially to the total global research and development expenditure.9 Authors in those countries, prompted by the pressure to publish, are increasingly availing themselves of language-editing services to avoid the possibility of rejection of their papers on grounds of poor language quality.4 This situation has spurred the establishment of many freelance editing companies and agencies and has prompted many journal editorial departments to shift from an in-house model to a freelance editing model with a view to reducing costs and improving the efficiency of the editorial process.5,6,10 Both models have obvious advantages and disadvantages. The chief benefit of an in-house model is that the quality of editorial output can be monitored and standardized through intensive and uniform training. However, the model cannot be scaled up, owing to the costs associated with managing an in-house team. A freelance model undoubtedly offers better cost effectiveness and flexibility10 and is supported by the availability of a large pool of subject-matter experts among various disciplines and across time zones and can thus serve as an efficient system for catering to increasing volumes of papers that require editing. However, because editorial styles can vary widely, a freelance model requires stringent quality control—a fact that has been recognized by various established publishers in the field of scientific, technical, and medical communication.5

To extract the benefits of both the above models and achieve an optimal balance of cost and quality, we adopted a combined freelancer–reviewer model involving a large pool of freelancers and a small team of in-house reviewers and assessed the quality of the resulting editorial output. With our evaluation method, we aimed to simulate the blinded peer-review process used by journals. To that end, we chose to assess clarity, language, and presentation—copy– editing–related aspects that peer reviewers would usually consider in evaluating manuscripts.11,12

Our results showed that the reviewed versions had significantly better language quality than the edited versions. That indicates that a two-editor team can more reliably produce high-quality editorial output than can a single editor; this is in line with Boomhower’s long-standing hypothesis that technical editing requires a two-step process that should be performed either by two persons or by the same person in multiple passes.7

ratings. Edited versions received poor ratings more frequently

than did reviewed versions except in clarity, in which the two versions received poor ratings with the same frequency. The difference in frequency of poor ratings was most prominent in presentation. 3-B. Edited and reviewed versions that

received excellent ratings. In general, reviewed versions

received excellent ratings more frequently than did the edited

versions on all parameters; this outcome was most apparent

in presentation

We also found that the reviewers’ contribution to the manuscripts was most prominent with respect to presentation, followed by language, whereas their contribution to clarity, although positive, was not significant. The ability to attain clarity through editing is determined largely by the editor’s understanding of the manuscript subject matter. In our model, the freelancers were subject-matter experts, whereas the reviewers, who had some background in the relevant broad subject fields, were trained specifically in language and presentation. Thus, our results strongly support our hypothesis and are consistent with Boomhower’s finding that tech nical editing is best achieved when one editor focuses on technical content, with special consideration of the target audience, and another focuses on language and the mechanics of copy-editing.7 That division of responsibilities is important in that two editors working on a single document might otherwise end up undoing each other’s changes or making contradictory changes owing to the arguably subjective nature of language editing.

On the basis of the assessors’ ratings, we classified each edited and reviewed version of the sample set as poor (score of 1 for any parameter or ≤6 overall) or excellent (score of 4 for any parameter or ≥10 overall), considering that a poor manuscript was likely to be rejected on grounds of language by a journal peer reviewer and an excellent manuscript would definitely not be rejected on grounds of language. Our finding— that the reviewed versions were rarely classified as poor and often classified as excellent—implies that the review process, by and large, improved the manuscripts to a publishable standard with respect to the parameters assessed.

An additional benefit of the present freelancer–reviewer model is that it can allow two-way exchange of information between freelance editors and centralized reviewers. That provides a channel by which freelance editors can receive reliable comments on the quality of their work; similarly, in-house reviewers can acquire subject-matter expertise by studying the changes made by the freelance editors.

Our study has some limitations. Although our results support the hypothesis that trained language editors can enhance the quality of manuscripts that have previously been edited by subject-matter experts, our quality assessment did not factor in whether the editors involved were freelancers or in-house employees. It is possible that the quality of the output would be the same if the roles of the two editors involved in the process were reversed; this could be a subject of future investigations. Moreover, it would be interesting for future studies to compare manuscripts edited by freelance subject-matter experts with those edited by in-house editors alone. Another limitation of the study is that the time spent by the freelancer and the in-house reviewer on each manuscript—a factor that could influence the quality of editorial output— was not considered in the quality assessment. Finally, a few papers received poor ratings even after review, and we were unable to explore the reasons for such a finding because this was a retrospective study; nevertheless, the finding implies that the editing and reviewing processes can be refined for better outcomes. Future studies could use an analysis that accounts for editing time and could explore technology-based or training-based methods to enhance the results attained with the combined model.

Conclusion

Our results support our hypothesis that a freelance editing model offers subject-matter expertise as its main strength, whereas a well-trained in-house reviewing workforce helps to implement strict control over language quality and presentation-related aspects of professional scientific editing. Combining freelance editing with in-house review can optimize the output achieved in language editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at Cactus Communications for their assistance with sample preparation and artwork design and for providing valuable suggestions that have enhanced this paper. Special thanks go to Aarti Khare and Priyanka Tilak for their help with statistical analysis.

Disclosure

Both authors of this paper are employees of Cactus Communications, which uses the freelancer–reviewer model described in the study.

References

- The Royal Society. Knowledge, networks and nations: global scientific collaboration in the 21st century. 2011.

- UNESCO. UNESCO science report 2010. The current status of science around the world. 2010.

- Iverson C. US medical journal editors’ attitudes toward submissions from other countries. Sci Ed. 2002;25(3):18–22.

- Kaplan K. Publishing: a helping hand. Nature. 2010;468:721–723.

- Pineda D. Editing ins and outs: the question of editing in-house or outsourcing. Sci Ed. 2004;27(3):86–87.

- Stanworth C, Stanworth J. Managing an externalised workforce: freelance labour-use in the UK book publishing industry. Ind Relat. 1997;28:43– 55.

- Boomhower EF. Producing good technical communications requires two types of editing. J Tech. Writ Commun 1975;5(4):277–281.

- Rosario D. Does having a non-English first language hinder competence in manuscript editing? Sci Ed. 2011;34(2):39. Abstract.

- Grueber M. 2012 Global R&D Funding Forecast: R&D spending growth continues while globalization accelerates. 2011 http://www.rdmag.com/Featured-Articles/2011/12/2012-GlobalRD-Funding-Forecast-RD-Spending-GrowthContinues-While-Globalization-Accelerates.

- Brand M. Outsourcing academia: How freelancers facilitate the scholarly publishing process [master’s thesis] Simon Fraser University; 1996.

- Byrne DW. Common reasons for rejecting manuscripts at medical journals: a survey of editors and peer reviewers. Sci Ed. 2000;23(2):39–44.

- Provenzale JM, Stanley RJ. A systematic guide to reviewing a manuscript. AJR. 2005;185:848– 854.