More people now have Facebook profiles than live in the United States. Facebook announced this statistic—that it has 350 million users—around the same time that the Oxford American Dictionary named unfriend its 2009 word of the year. Unfriend is defined as “to remove someone as a ‘friend’ on a social networking site such as Facebook”.

Are journals joining the social-media frenzy?

The short answer is yes, but determining exactly how different journals do so is surprisingly difficult.

To begin, social media refers to Web content created by users and exchanged with others. The phrase is associated with Web 2.0, or the “second generation” of the Internet, which emphasizes collaboration. With such an overarching definition, what does social networking by a journal look like? Any social media sponsored by the publishers of a scientific journal? Only those aimed at scientists? Perhaps the social-networking features must be directly related to the journal articles?

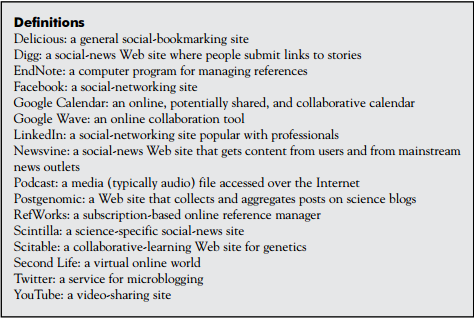

Furthermore, social media, a term often used interchangeably with social networking, implies a heterogeneous mixture of platforms and Web sites. Scholarly journals most commonly use blogging, microblogging, social networks, and social bookmarking.

Blogging is derived from blog, which is a shortened form of Web log. A blog is an online journal, or log of events, thoughts, feelings—or anything else the writer chooses. It can be updated several times a day or once every few months. It can be written by a single person or by a group of people. It can have a specific topic or consist of random thoughts. There are a variety of blog-hosting Web sites, or a person can create one on his or her own page.

Microblogging is similar to blogging but, as the name implies, on a smaller scale. Users typically write very short messages, updates, or thoughts. For example, Twitter, the quintessential microblogging service, limits posts to 140 characters—the maximum length of a cellular-telephone text message.

When Facebook began, it was envisioned as acting almost as a yearbook, in which students could look up their classmates and find some basic information about them, such as their hometowns and majors. The networking aspect of it comes from the ability to add people as Facebook friends, who then have their friends, who have their friends, ad infinitum. Facebook has since exploded with new features, called applications, but the basic premise remains. LinkedIn is a similar site but with a more professional focus.

Social bookmarking is a way of sharing interesting things with others and using others’ lists to discover new information. For example, such sites as Delicious allow users to post the URLs of interesting Web sites and then assign each one a “tag”—a short descriptor. People can then search for a word—genetics, for example—and the Web site will present a list of every site someone has tagged with the word genetics. Social bookmarking can also be a way of sharing a Web site with one or more friends. In addition, users can find new sites that they might enjoy on the basis of an algorithm that compares their lists with other people’s (this is similar to how Amazon uses “customers who viewed this also viewed . . .”). There are also several social-bookmarking services specifically for journal articles; such services include Springer’s CiteULike (www.citeulike.org), Mendeley (www.mendeley.com), and Nature Publishing Group’s Connotea (www.connotea.org).

However, those terms have few defined boundaries. For example, Facebook has features of microblogging: users can write “status updates” that post to their “walls” and to their friends’ newsfeeds. Thus, this feature of Facebook functions very much like Twitter. Users can also post a URL to their walls for friends to view, and this makes Facebook function like a social-bookmarking site.

Perhaps the clearest way to define social media is to explain what it is not. It is not simple sharing of information: The flow of information must go both ways, like a conversation, not a speech. Therefore, RSS feeds (which journals commonly use) are not really social media. Furthermore, posting updates on a Web site, regardless of frequency and content, does not really constitute a blog unless readers can interact (in some way) with the author, usually by leaving comments.

Basic Efforts at Social Networking

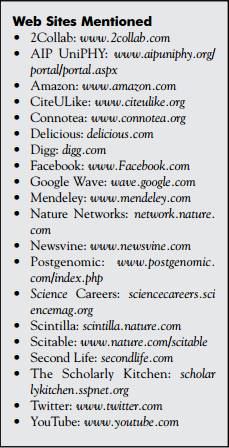

Using established social-networking Web sites is a common, relatively easy way for a journal (or anyone else) to begin social networking. (CSE now has presences on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter.) Journals tend to use the ones that are most popular in society at large—Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. The American Journal of Critical Care, the Archives of Neurology, BioMed Central, the Journal of Cell Biology, the Journal of Experimental Medicine, the Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry, Pediatrics, the New England Journal of Medicine, Science, and the beta version of the Journal of the American Chemical Society (no doubt there are many others) have Facebook pages.

A Facebook page can be thought of as the profile of a business or organization— for example, a journal. It must be categorized as education, Web site, business, nonprofit, or one of several other options. Creating a page takes only a few minutes; however, maintaining a good one tends to require continual work. In addition to basic information about the journal, a journal’s page can contain photos, videos, a calendar of events, links to other Web sites (such as the journal’s Twitter page or home page), or pretty much anything else that the creator of the page chooses. To create a vibrant community, though, someone must periodically post new messages to the page’s wall. The messages might be news related to the journal or the journal’s discipline, links to articles, or anything else that the moderator deems important or interesting. Facebook users can become “fans” of a page (to receive updates on postings), post comments, and suggest the page to friends.

Physical Review D does not have a Facebook page, but a Facebook group. Groups have been part of Facebook for years; pages are much newer. Groups are less independent than pages; they must be begun by a person with his or her own profile. Furthermore, people aren’t fans, they are group members—maybe an unimportant distinction of terminology, but perhaps, at least symbolically, indicating the level of involvement that users can have.

When this article went to press, the New England Journal of Medicine had three Facebook applications in beta testing: popular articles, recent articles, and podcasts. Applications are like little programs that operate within Facebook.

Twitter is also widely used: Science and Cell Press are two examples that are actively involved. The Journal of the American Chemical Society has also experimented with its use.

The New England Journal of Medicine, Cell Press, and others have created YouTube channels, which feature video clips related to the topic of the journals. Those pages are often difficult to find simply by searching YouTube or Twitter, even with very specific search terms. It is far easier to approach them from a journal’s Web site. The Journal of Chemical Physics makes it especially easy for users: on its home page, under the heading “Web 2.0 Tools”, users can access its pages on Twitter, YouTube, Google Calendar, and so on.

The different sites of a journal are often linked to each other; for example, a journal’s Facebook page may direct users to its Twitter account and YouTube channel. That might not reflect an overarching plan for social networking at each journal. Stewart Wills, online editor at Science, says he thinks that these efforts have often “grown organically” over time.

Some journals use third-party services to add social-networking features directly to their journal articles. For example, the Journal of the American Chemical Society offers readers of its articles the following options, under the heading “Recommend & Share”: e-mail, save, “Digg This”, send to CiteULike, send to Delicious, post to Facebook, and post to Newsvine. Digg and Newsvine are social-news Web sites— essentially, users submit links to stories, on which others can vote or comment.

Similarly, PLoS One has links in each of its articles to “share this article”, using Facebook, Connotea, CiteULike, Digg, “regular” e-mail, and others. PLoS One also makes its articles interactive directly on its Web site. Users can comment on and rate each article and easily find referenced articles from the included hyperlinks.

The New England Journal of Medicine embeds commenting and polls (related to the topic at hand) next to at least some of its videos. Science allows commenting on its daily news stories but not on its scholarly journal articles. Perhaps not coincidentally, recent daily news stories are freely available, but access to most journal articles requires a subscription.

Cell recently implemented an interactive approach to the viewing of articles on its Web site. All the citations are hyperlinks to the full listing of an article. Furthermore, readers can send their thoughts on the article (and even include YouTube videos as part of their comments); the ones that the editors deem relevant are published in the comments section.

Advanced Efforts

Journals are beginning to go even further toward developing their own social-networking tools. For example, when this article went to press, the Journal of the American Chemical Society was beta testing a Journal Club (essentially a blog featuring news, questions and answers, and tips from other researchers).

Elsevier has its own social-bookmarking site, called 2Collab (which has in the past come under spam attacks and had to shut down temporarily for repairs). 2Collab allows users to create a library of references by importing bookmarks from a Web browser or from Delicious, and references can be imported and exported to RefWorks and EndNote.

Science Careers, an offshoot of Science, offers two social-networking sites—one for those from “diverse backgrounds” and one for those in clinical fields—and a forum for general discussion of employment and career development in the sciences. Science’s Web site also offers blogs on a variety of topics that include careers but also science policy and reports from scientific meetings.

The American Institute of Physics recently launched AIP UniPHY, which is a social and professional networking site for physicists. According to Chris Iannicello, AIP UniPHY’s product manager, the site “enhances and accelerates the collaborative process among physical-science researchers”. The site has a prepopulated profile of people who have published, in the last 10 years, at least two articles listed in the Searchable Physics Information Notices database. But membership is open to anyone, so even novice researchers can find out “who we are suggesting are the primary players within specific scientific disciplines”, Iannicello says. The site is also designed with editors in mind: “I think that AIP UniPHY can assist journal editors,” Iannicello says, “making their job of finding peer-review candidates easier.”

The social-networking efforts of the Nature Publishing Group (NPG) far outpace all those in terms of number of separate platforms and in complexity. In addition to those mentioned above (Facebook page and Twitter site), NPG runs property in Second Life, an online virtual-reality world; Connotea, a social-bookmarking site for scientists; Postgenomic, which collects and aggregates popular science blog posts; Scintilla, which is similar to Postgenomic, but also gathers science stories from mainstream media with science video, podcasts, and job postings; Nature Networks, a social-networking site for scientists that includes forums, blogs, events, and job listings; and Scitable, a networking site aimed primarily at students and professors.

With the tagline “Learn Science at Nature”, Scitable takes the concept of social networking, already familiar to undergraduate students, and uses it to connect them to such resources as scientific articles and experts willing to answer questions. According to its Web site, Scitable’s goal is to “fuel a global exchange of scientific insights, teaching practices, and study resources”. As of early 2010, Scitable had information only on genetics, but its editors said that they plan eventually to expand it to more of the life sciences and to target other audiences.

Scitable illustrates a difficulty in characterizing journals’ use of social networks: Is the site a part of the journal Nature, or is it a loosely related spinoff? If the main audience is undergraduates and their teachers, what does it have to do with original scientific research? Of course, because most university science professors are practicing scientists, this line becomes a bit blurry.

Issues for Publishers and Editors

Several issues come into play in deciding how, or whether, a journal should become involved in social networking. While the debate continues about how much social media can or should be involved in scholarly publishing, here are a few things to consider:

One major consideration is the workload of the staff—is there money to hire someone specifically to coordinate social networking? If not, how should maintaining the journals’ social-networking site(s) be factored into the workload of a current staff member? All too often, monitoring and moderating social-networking pages create an unfunded mandate for people’s time.

One major consideration is the workload of the staff—is there money to hire someone specifically to coordinate social networking? If not, how should maintaining the journals’ social-networking site(s) be factored into the workload of a current staff member? All too often, monitoring and moderating social-networking pages create an unfunded mandate for people’s time.

Social media can also introduce new legal issues. Generally speaking, in the United States, the provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act protect the host of a Web site from liability for users’ postings that violate copyright laws. However, the protection is subject to conditions, so it might be useful to consult an attorney, especially inasmuch as different countries have different laws. It is also important to remember that a journal might be liable for whatever its employees post on the site.

Given those concerns, the question becomes whether involvement in social media is worth the difficulties. Perhaps one way to approach the question is to think about the goals of any social-networking endeavor. In other words, what does “success” look like?

Looking at how or whether social media will support the mission of a journal is one way to measure success. Some journals seem to address this directly. For example, Scintilla’s Web site gives Nature’s mission statement and then says, “We think Scintilla helps us to achieve these goals [in Nature’s mission statement].”

Jose Fernandez, who works on the socialnetworking aspects of Science Careers, says that he thinks his work does the same for Science. “I believe Science Careers benefits the mission of the journal Science by helping develop prominent new researchers that will take the torch and continue contributing world-class scientific research,” he says. “I try to develop meaningful connections among the young scientists and upcoming trainees. The connections that will hopefully lead to breakthrough collaborations that will enhance the body of scientific research.” Still, Fernandez acknowledges that it can be difficult to gauge success. “It’s hard to measure ROI [return on investment] in a social network,” he says.

Finally, an issue that is affecting society at large: As we move from disciplined print media to a collaborative, democratic approach to information, how do experts maintain their status as experts? Social networking inevitably means giving up some control of the product and the brand to users, and this leads to some degree of unpredictability and risk.

Are Scientists Using Social Media?

What about scientists, though—are they using these tools, or other social-media sites, in their professional lives? What types of features do scientists need or want? There has been little market research to answer that question, but anecdotally it appears that many scientists are not using the tools that are available. In March 2007, Richard Apodaca, a chemist, titled a blog post “Why I Still Don’t Use Connotea”. In a recent interview, Apodaca elaborated, saying, “I wasn’t really seeing what the value added was” over more traditional reference-management software or even the classic hard-copy-and-folders system. “What does it add to your productivity in managing these references?”

It seems that he’s not the only one wondering. David Crotty, executive editor of Cold Spring Harbor Protocols, commented (in a post to the Society for Scholarly Publishing’s blog The Scholarly Kitchen) on the “lack of compelling reasons to participate” in scientific social-networking sites. Crotty also noted his impression that biologists, at least, did not find such sites useful.

Part of the problem is site developers’ lack of understanding of the culture of science, Crotty said. “Any network that hopes to succeed must adapt to the culture of the community, rather than trying to rewrite it,” he said in a blog post.

Scientists are wary of the term networking, Apodaca says. For a site to work, he believes, it must have “social networking as a feature, not a destination”, inasmuch as networking and collaborating over the Internet tend not to be vital parts of a scientist’s work on a daily basis.

“You go into a specialty and that’s what you really care about,” says Apodaca. “You’re not so much interested in general science things.”

Still, millions of people—in myriad professions—are registered on Facebook. Some of them are scientists. In a comment posted to The Scholarly Kitchen, paleontologist Andy Farke said, “Among a significant percentage of vertebrate paleontologists, Facebook has become the social networking medium of choice. It’s pretty widely used, by a diverse cross-section of the field.”

Other scientists use it, too: There are “users on the Fan Page [for Science Careers] ranging from undergraduates to established senior scientists,” Fernandez says.

Twitter is also being used by the scientific community. An article by Laura Bonetta, a science writer and editor, in Cell on 30 October 2009 discussed the use of Twitter by scientists. “Disseminating scientific information is a driving mission for many Twitter users,” wrote Bonetta. In fact, reporting scientific conferences on Twitter (without prior permission by the presenters) has been the cause of some controversy, because scientists might not want their work so widely publicized yet, according to the article.

Perhaps that use of the established social-networking sites is part of why science-specific sites do not seem widely popular. “There’s no point in duplicating the functionality of bigger, stronger, more functional networks for a smaller community—you lose the network effects and you don’t gain any new functionality,” posted Crotty on The Scholarly Kitchen.

The short answer to whether scientists use social media is that we just don’t know, according to a post by Kent Anderson, publisher of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, on The Scholarly Kitchen. Anderson added, “Yet, it seems scientists are finding value in social tools, and are moving into social networking.”

The Future

Much debate has focused on whether social media will become more used in science and scientific publishing as younger people enter the profession. Some take it as a given that these young scientists, having grown up using social-networking programs, will expect to use them in their careers. Iannicello says that as younger generations grow to the point of being graduate students, they will have an “expectation of a multitude of Web x.0 features to be available”, and it is important for his team (and other creators of social media) to “stay ahead of the curve in developing these cutting-edge features”. Not everyone is as certain, though, that the next generation of scientists will change the scientific community’s use of social media.

Much debate has focused on whether social media will become more used in science and scientific publishing as younger people enter the profession. Some take it as a given that these young scientists, having grown up using social-networking programs, will expect to use them in their careers. Iannicello says that as younger generations grow to the point of being graduate students, they will have an “expectation of a multitude of Web x.0 features to be available”, and it is important for his team (and other creators of social media) to “stay ahead of the curve in developing these cutting-edge features”. Not everyone is as certain, though, that the next generation of scientists will change the scientific community’s use of social media.

David Crotty posted on The Scholarly Kitchen:

Early graduate students have the least to offer any social network. They haven’t yet done the research, so they have little by way of results to communicate, they’re unlikely to be in charge of setting up collaborations for the lab and because of their inexperience, have the least practical advice for others. By the time they can offer useful contributions to a network, they are likely to be too busy to spend much time on a network and will probably be indoctrinated into the more traditional ways of networking.

Who knows, though, what effect new technologies will have? Google Wave, a new collaboration application, has the potential to shake up, once again, the concept of social networking.

This article has been a snapshot of what some journals in the United States and Britain are doing with social-networking tools. As technology evolves, the picture is likely to change, so social networking is something for editors around the world to monitor.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Stewart Wills for his invaluable help in researching this article.