Introduction

The Peer Review Innovations workshop at this year’s Researcher to Reader Conference in London brought together 30 colleagues from various facets of scholarly communications, including publishers, institutional librarians, open research advocates, consultants, and service providers. In keeping with the overall ethos of this popular annual industry event, our collective goal was to share insights from across the scholarly community and to explore possible innovative ideas that could help improve peer review for all stakeholders engaged in this process.

Setting the Scene

Before discussing ideas to improve peer review, the workshop agreed on the parameters for our discussions, defining peer review as the timeframe between the submission of research to a journal or other platform for publication, and the editorial decision by that journal or platform to publish the work. Whilst not a perfect or all-encompassing definition, this was intended to give a workable frame of reference to the workshop participants for the three 1-hour sessions during the 2 days of the conference.

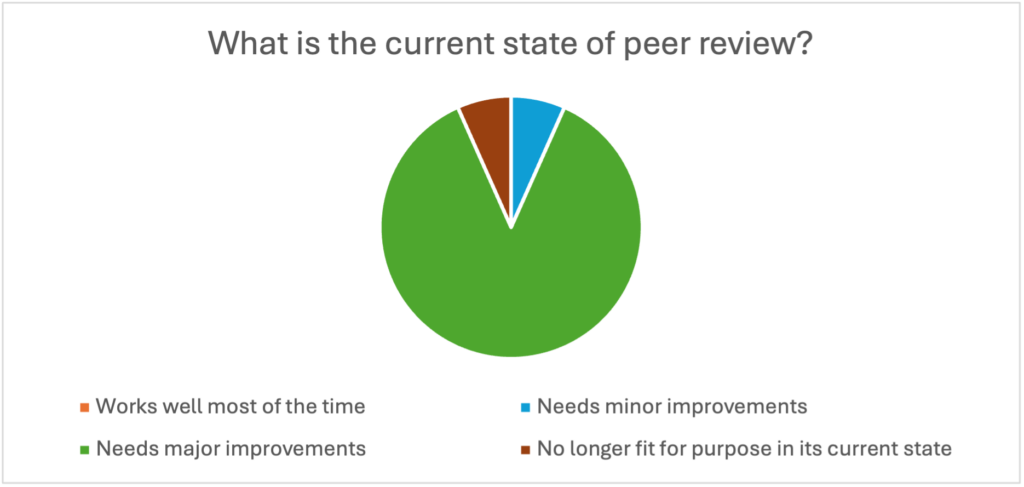

We also discussed the current state of peer review, asking the participants to vote for 1 of 4 options. The vast majority of the group (93%) felt that peer review is in need of major improvements to meet the needs of its various stakeholders (Figure 1). Noone in the group felt that peer review in its current state is working well most of the time—perhaps unsurprising in a workshop dedicated to discussing peer review innovations!

This exercise not only illustrated the participants were aligned in their perception that peer review requires a major rethink, it also created a sense of urgency and purpose in the room.

Threats, Pain Points, and Successes

In session 1, the workshop participants, working in 5 groups, were asked to list the threats, pain points, and successes (described during the session as “things that work well”) in peer review in its current state. The workshop participants collectively prioritized the following main threats, pain points, and successes:

Threats

- Generative artificial intelligence (AI): fake papers, fake people, fake everything

- Integrity: fake journals, fake papers, fake reviews

- “Publish or perish” culture: institutional incentives

- Deficiencies in scholarly rigor and ethics

- Misconduct

The consensus from the group was that the culture of publish or perish incentivizes misconduct, and generative AI provides readily available tools that make misconduct easier.

Pain Points

- Proof of identity and lack of industry collaboration for identity management

- Finding reviewers due to lack of training and a lack of standards/consistency

- Overloaded teams and systems: crumbling under pressure, working with small reviewer pools and too many papers

- Finding suitably qualified peer reviewers

- Time pressure for researchers and peer reviewers

The overall sense was that the difficulty in finding qualified reviewers is exacerbated by the inability to fully trust reviewer identity, which is related to the lack of knowledge about possible reviewers outside of mainstream western institutions.

Successes

- Concept of peer review: cumulative trust indicator

- Open peer review: can this help with trust?

- Longevity: peer review has been around for over 100 years; hard to make a behavior change

- Improves science

- Using AI tools to find peer reviewers

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the participants found it easier to identify specific threats and pain points than specific successes, which were more thematic in nature. Fundamentally, peer review is a strong and valued concept; it signals trust and improves science, but its mechanics need major attention to cope with the numerous threats and pain points.

Gaps and Innovations

Session 2 asked the participants to think about what would enable “perfect peer review”: focusing on gaps that need addressing, current successes that can be enhanced or extended, and areas for innovation and new thinking.

The session used an adapted version of the “1-2-4-All” framework for generating, discussing, and refining ideas—in this case, “1-2-Table” for each of the 5 groups. Starting with individual ideas, participants then discussed their respective ideas in pairs before coming together as a table to prioritize their top 5 ideas.

Key themes from this session were the following: changing culture and incentives upstream from the peer review process; embracing technology that can be trusted as being critical and reliable, rather than purely generative; creating and adopting industry standards; and a push toward prompt, effective, and constructive peer review.

Practical Solutions and Blue-Sky Thinking

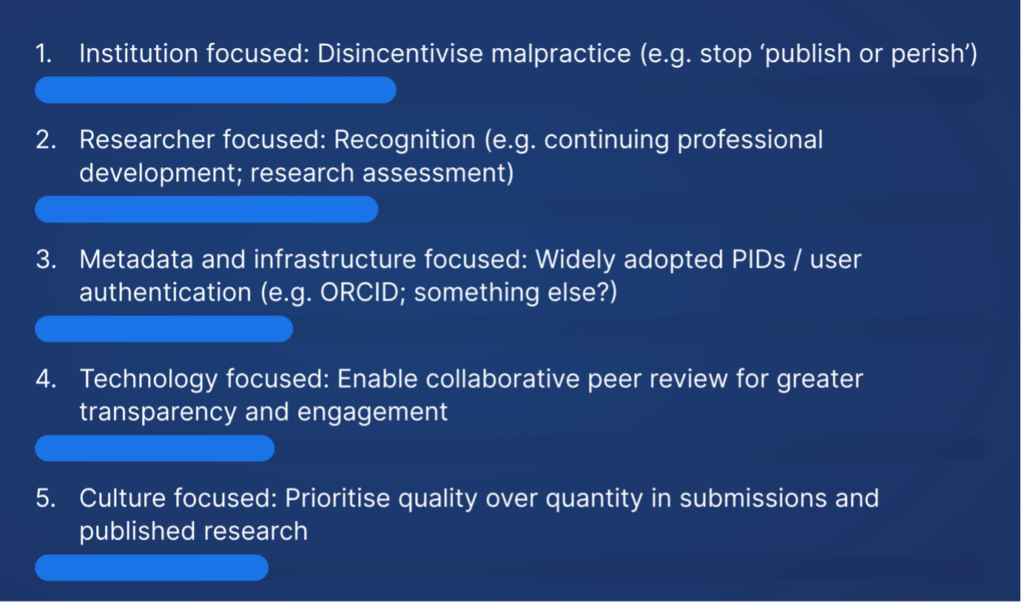

At the start of session 3, the various ideas shared by each workshop group in session 2 were categorized for a Slido poll in which participants were asked to rank their top 5 ideas in order of preference (Figure 2):

Researcher Focused

- Formal training and mentoring for early career researchers

- Recognition (e.g., continuing professional development, research assessment)

- Monetary incentives (e.g., paid-for peer review, article processing charge discounts)

- Foster a community of peer reviewers to share experiences and best practice

Institution Focused

- Provide researchers with the space, time, and resources to undertake peer review

- Formal training for researchers

- Disincentivize malpractice (e.g., stop publish or perish)

- Recognize peer review in researcher career development

Metadata and Infrastructure Focused

- Widely adopted persistent identifiers (PIDs)/user authentication (e.g., ORCID, something else?)

- Easier, more efficient metadata capture throughout the workflow

- Infrastructure to support portable peer review

Technology Focused

- Reduce friction and delays in the peer review workflow

- Automated tools to reduce administrative burden on journals when triaging submissions

- Automated integrity checks upstream, presubmission

- Automated reviewer finding and matching tools

- Embrace AI as part of undertaking the review process

- Enable collaborative peer review for greater transparency and engagement

Culture Focused

- Recognize and engage with differences in the culture of peer review globally

- Prioritize quality over quantity in submissions and published research

- Take a longer-term view on the research lifecycle

Top 5 Areas for Innovation

The workshop participants voted for the following top 5 areas, and each group was assigned 1 of these ideas to discuss: (1) practical actions that individuals and their organizations can take immediately; (2) realistic medium-term actions for adoption by the scholarly communications community; and (3) blue-sky ideas if money, resources, and time are no obstacle.

It is interesting that the bottom-ranked idea (no. 20) was that of monetary payment for peer review. Whether this reflects wider industry sentiment, or just the collective view of the 30 participants voting on these 20 specific ideas, is a moot point.

Disincentivize Malpractice

Immediate Practical Actions

- Greater awareness and education across the scholarly community

- Campaigning by industry bodies

- Greater volume and consistency of resources between publishers

Realistic Medium-Term Actions

- Greater consequences for malpractice at an institutional level—monetarily and reputationally

Blue-Sky Thinking

- Stop publish or perish!

- That being said, there will always be a push for some form of relative measurement of researchers and institutional research performance—will bad actors simply find ways to game the alternatives?

These solutions point to a consensus that researcher malpractice stems from institutional incentives and that it is the researcher’s organization that is ultimately responsible for monitoring and punishing bad actors. Publishers can police the process, and tools can be developed to aid the publisher in that process, but it is the researcher’s employer who has the greatest sway over researcher behavior.

Recognition

Immediate Practical Actions

- Extend current initiatives such as CoARA, ORCID Peer Review Deposit, and ReviewerCredits

- Improve the level and consistency of feedback provided to peer reviewers

Realistic Medium-Term Actions

- Devise more effective measures for quality control in peer review—reviewer rankings?

- Funder-driven initiatives for recognizing peer review contributions

- Enable readers to provide feedback—affirmative or critical—in open peer review and post-publication peer review

Blue-Sky Thinking

- Extend peer review quality measures upstream to institutions to encourage them to value and recognize the time spent by their researchers in undertaking peer review

Professionalization of peer review appears to be the solution across all categories. Today peer review is seen as a volunteer activity, done on one’s own time. Implementing training, carving out time during working hours, and institutionalizing recognition for researchers who engage in peer review might go a long way to increasing the willingness of researchers to perform this important service. Interestingly, as noted above, there is little support for actually paying peer reviewers for their efforts. This may be a result of the demographics of the participants, which was largely publisher-centric.

Widely Adopted PIDs and User Authentication

Immediate Practical Actions

- More widespread (ideally near universal) adoption of ORCID by scholarly publishers

Realistic Medium-Term Actions

- Funders to contribute to the financing of widespread/standardized PID adoption as part of their investment in safeguarding the version of record

- Use PIDs such as ORCID to track and share data on aggregated quantity of reviewers

- Use PIDs such as ORCID to disambiguate reviewer identities and to engage with previous reviewers

Blue-Sky Thinking

- Globally standardized metadata—for instance, on article types, institutions

- Interoperable peer review standards

In many ways, the solutions are already in place but are clearly underutilized for a variety of reasons. For example, ORCID was enthusiastically embraced early on, and usage continues to grow; however, although we would like to see even wider adoption, a bigger value add for publishers would be some element of verification at ORCID, like the Know Your Customer protocol in financial services. Then, we could be confident that the person we are communicating with is the right person and not an imposter. Similarly, NISO, Crossref, and other organizations maintain and promote standards for metadata and recently, a Peer Review Terminology Standard was developed jointly by STM and NISO. The challenge is getting the entire ecosystem utilizing these standards, especially funders and institutions.

Collaborative Peer Review

Immediate Practical Actions

- Consider for adoption on specific journal titles

Realistic Medium-Term Actions

- Create a taxonomy of reviewer contributions—ideally as an extension of CRediT for author contributions—for a more holistic view of researcher activity in scholarly communications

Blue-Sky Thinking

- Develop an industry platform (or platform standard) that supports collaboration, transparency, engagement, and equity among all stakeholders in the peer review process

Similar to recognition, collaboration focuses on the peer reviewer as the central character. Because peer review is usually a solo endeavor and tends to take place in the dark, the activity is seen as a burden, and there is increasing mistrust in the process. Finding ways to open up the evaluation process, introducing more collaboration, and allowing (acknowledged) early career researcher participation might be solutions to these issues.

Prioritize Quality Over Quantity

Immediate Practical Actions

- Improved submission software systems

- Ensure researchers are choosing the right journal or platform for their research

- Reduce the focus on publishing at volume

Realistic Medium-Term Actions

- Quality is subjective—we need a consistent or standardized definition of what constitutes a high-quality submission

- Train scholars on writing effective abstracts

- Move away from a seemingly endless cascading process used by some publishers to retain submissions within their portfolio

- Look at the motivations behind researchers submitting too many papers to too many journals

Blue-Sky Thinking

- Change the incentives driving publish or perish

- Develop standardized abstract analysis tools for faster and more accurate triage and peer reviewer identification

- Adopt a “two strikes and out” industry rule for submitted research—if a submission is rejected by 2 journals, irrespective of publisher, it cannot be considered by any other journal. How workable is this idea?

The final area for innovation is perhaps the hardest to achieve since it involves an overall cultural change in how research is published and the incentives that drive researchers to publish. Reducing “salami-slicing” and limiting cascading are tactics, but the larger solution, again, lies with funders and research institutions who reward quantity.

There are vast differences in how research is conducted and reported across disciplines, including unique cultural idiosyncrasies and discipline-specific traditions, making standardization challenging. There is also an indication that technical systems need to modernize to deploy more AI-type tools to identify and fix quality issues, but like the previously mentioned challenge, there are many players, many different technologies, and many varied requirements from discipline to discipline.

Summary

The most potentially contentious innovation from the workshop is the final one discussed by the participants and shared here, the “two strikes and out” idea. It will be interesting to see if the idea of restricting the number of times a paper can be submitted to any journal, before it effectively becomes void, is either desirable, workable, or fraud-proof. It would certainly require industry collaboration and technological capabilities to support such a move. And would it be regarded as being in some way prejudicial toward certain authors or global regions? These considerations notwithstanding, it was certainly fun to end the workshop with such a hot topic for discussion and further debate!

Having established our parameters, defining peer review as the timeframe between the submission of research to a journal or other platform for publication, and the editorial decision by that journal or platform to publish the work, and having established consensus during the first exercise—that peer review needs major improvements—the participants were quite productive identifying threats and pain points, while struggling to come up with specific answers to what are some successes. Settling on the concept of peer review as a success, this motivated the room to find solutions to secure its foundations and build a better infrastructure. There were many ideas for specific innovations, like better use of PIDs, ORCID, reviewer recognition, and quality assessment tools.

However, there was overwhelming recognition that the biggest change factors are institutions and funders who control the purse strings and manage the reputations of researchers. Publishers who manage the peer review process can create rules and utilize technology to improve peer review, but the innovation that might make a difference lies with changing the publish or perish culture that drives researchers to overwhelm the system, create peer reviewer shortages, and foster mistrust of science.

We hope this workshop provided food for thought for the participants and for the wider scholarly communications community. We look forward to ongoing collaboration with colleagues as we take these themes forward in future discussions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the workshop participants for their wholehearted contributions to the conversations, debates, and outputs. We are also extremely grateful to Mark Carden, Jayne Marks, and the Researcher to Reader 2024 Conference organizing committee for the opportunity to develop and deliver this workshop.

Reprinted with permission from the authors.

Tony Alves (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7054-1732) is with HighWire Press; Jason De Boer (https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6940-644X) is with De Boer Consultancy and Kriyadocs; Alice Ellingham (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5439-7993) and Elizabeth Hay (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6499-5519) are with Editorial Office Limited, and Christopher Leonard (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5203-6986) is with Cactus Communications.

Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Council of Science Editors or the Editorial Board of Science Editor.