MODERATOR:

Jennifer Mahar

Managing Editor

Origin Editorial, part of KGL

Editorial Evolution

SPEAKERS:

Paul Graham Fisher

Professor of Neurology and Pediatrics, Stanford University

COPE Council Member

Editor-in-Chief, The Journal of Pediatrics

Sara Kate Heukerott

Associate Director of Publications

Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)

REPORTER:

Madeline Talbot

Associate Editor

Wolters Kluwer

Each year, the CSE Annual Meeting hosts an Ethics Clinic sponsored by the CSE Editorial Policy Committee. In this interactive session, speakers present real-life cases to facilitate group discussions of ethical dilemmas that arise in scholarly publishing. Attendees discuss potential approaches and solutions, and speakers share strategies and case outcomes. This year’s Ethics Clinic expanded on the meeting’s focus on AI in scholarly publishing.

Key Takeaways

- AI is not going away; the use of AI by authors, reviewers, editors, and publishers is inevitable. Stigma toward AI will only make scholarly publishing’s management of it more difficult. By understanding and embracing AI, scholarly publishing can ensure it is used ethically by all parties.

- Clear and detailed AI policies for authors, reviewers, editors, and publishers are crucial. An AI policy should be a living document that changes as the technology and its uses continue to develop. AI policies for scholarly publishing should define what uses of AI and which AI tools and large language models (LLMs) are acceptable. Policies should also outline when disclosure of AI use is required.

- Transparency is vital. AI use should be disclosed by authors, reviewers, editorial offices, and publishers alike. Disclosure can help all parties determine whether AI use was ethical, or whether further investigation into its use is necessary.

Case 1: Suspected AI Use by the Author of a Manuscript

In the first case presented by Dr Paul Graham Fisher, a council member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), a journal received a reviewer report that identified suspected AI-generated content in a manuscript. The reviewer had uploaded the manuscript to an open AI checker without the journal’s permission, and the tool indicated that 75%–82% of the article was AI-generated. This raised ethical and procedural questions for the journal, including whether reviewers can run manuscripts through AI checkers and whether suspected AI use should be included in reviewer comments to the author.

Discussion participants questioned whether the journal had an established policy that outlined what AI use is permitted for both authors and reviewers, including whether the reviewer had breached confidentiality by uploading a submission to an open LLM. Having a clear, detailed AI policy can make it easier to determine whether AI use was inappropriate or within the journal’s acceptable boundaries. For example, some journals may allow authors to use AI for grammar checks, but not for content generation. Specificity in a policy is crucial for all parties.

In this instance, participants also discussed the need to tell the author that their submission had been shared with an open LLM, if that was in fact a breach of the journal’s established policy. This may not be a pleasant conversation, but the transparency is necessary. The audience and speakers agreed that in this case, and in most AI-related cases, communication here is key: Journals need to be clear with their authors and reviewers on what their specific AI guidelines and expectations are. Reviewers should also understand that AI checkers are not foolproof and are fallible. Dr Fisher noted that it is nearly impossible to “detect properly and definitively AI-generated text.” He also recommended that if a journal is considering changing a peer reviewer’s comments about AI usage to an author, they should first review COPE’s guideline on editing peer reviews.1

Case 2: Journal Under Attack with Bombing of AI-Generated Manuscripts

Dr Fisher also presented the second case, which explored an instance in which a journal received an influx of AI-generated articles, ranging from nonsensical submissions to highly sophisticated fakes that were difficult to detect. This surge strained the journal’s editorial office, leading to concerns about how journals with limited resources can defend against AI-driven submission attacks.

This scenario was not unfamiliar to the audience; one audience member shared that their journal had experienced a similar situation in which they had to desk-reject the same AI-generated submission nearly 30 times. In that case, even reaching out to the author directly to ask them to stop did not work. The burden of this can be immense for editorial offices that are already stretched thin or lacking sufficient resources.

Discussion revolved around AI-detection technology, similar to what is currently available to detect papermill submissions, that may become more widely available in the near future. Some audience members were concerned that high-quality detectors will not be equitably available to all journals and publishers with smaller budgets, perpetuating publishing’s “pay-to-play” environment. Submission fees even as low as $1 or $5 could discourage these types of attacks, but also pose risks, such as isolating international authors who cannot afford those costs. More questions were raised, such as whether AI attacks like the one presented would skew journal rejection rates, or whether it was possible that AI attacks like this one were being done by authors to test whether a journal was predatory.

Although there was no definitive conclusion on how best to handle AI-generated manuscript attacks, the speaker noted that cases like these could be escalated into a civil lawsuit against the author behind the attacks. If a journal is going to involve legal counsel, a clear AI policy must already be in place to determine whether the author’s actions are malicious and in breach of that policy.

Case 3: Suspected AI-Generated Peer Review Reports

The session’s third case was introduced by Sara Kate Heukerott from the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). In this case, a reviewer for an ACM-published conference submitted an unusually high number of reviews—more than 20—while also being an author for the same conference. The reviews followed a distinct pattern, including lengthy responses with section headings, bulleted lists, and general remarks. In one instance, the reviewer’s notes included critiques of statistical analysis that did not exist in the submission. This raised concerns about the integrity and authenticity of the reviews.

Many questions were raised during the discussion period, including whether this reviewer/author was known to the conference committee and whether ACM vets their peer reviewer pools. Vetting peer reviewers allows journals and conference organizers an opportunity to communicate expectations and reviewer guidelines and share any existing AI-policies that outline acceptable-use for peer reviewers. There are many reasons why a reviewer may use AI as a support tool that are not necessarily malicious; one audience member suggested the reviewer may be early-career and unfamiliar with reviewer expectations or the conference’s policies. Some also felt that the fact that the reviews were potentially AI-generated was a moot point, as a bad review is a bad review, no matter the source.

This case concluded with the audience in agreement that the conference committee needed to communicate journal standards to the reviewer, highlighting concerns about the lack of specifics and the critiques of nonexistent content in their reviews. Heukerott shared that in this case, ACM contacted the reviewer who explained that they were a student looking for ways to contribute to the conference. They claimed that they had completed the reviews over a series of weeks and had used ChatGPT to check and improve their work. After deliberation, the Ethics & Plagiarism committee did not feel that the reviewer entering their reviews into ChatGPT was a breach of confidentiality because the information in the reviews was generic. Because there was no policy violation, the committee determined there was nothing they could do in this situation except to do further educational outreach to their communities to safeguard against this in the future. Without clear and specific AI policies for both reviewers and authors, investigations into cases like these can cost organizations immense amounts of time to determine whether suspected AI use was “right” or “wrong.” Encouraging disclosures of AI use can also eliminate confusion in these cases.

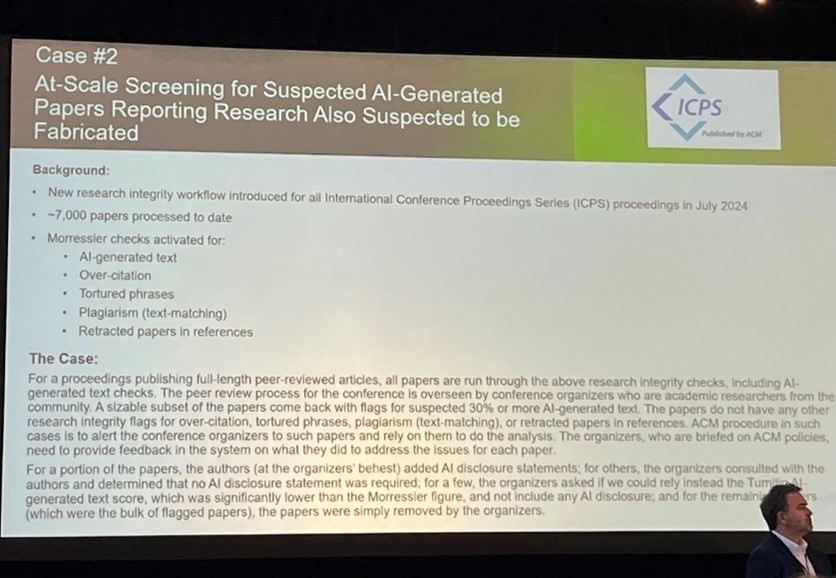

Case 4: At-Scale Screening for Suspected AI-Generated Papers Reporting Research Also Suspected to be Fabricated

The fourth and final case, also introduced by Heukerott, focused on the increasing need for rigorous vetting of academic papers to ensure authenticity and research integrity (Figure). The case involved the proceedings of a conference that is not run by ACM but whose proceedings are published by ACM. For such proceedings, ACM requires organizations to reapply annually to publish their proceedings with ACM. Every manuscript undergoes full-length peer review, and all peer-reviewed submissions are assessed using AI checker tools. If content is flagged, ACM sends it to the conference organizers for further scrutiny. In this case, a substantial number of already-accepted conference papers were flagged for containing more than 30% AI-generated text, according to a Morressier integrity product.2 When ACM brought this to the attention of the organization hosting the conference, the organizers requested that all accepted materials be checked again using TurnItIn instead of Morressier as the verification method. This raised further questions about the reliability of different AI detection tools, which may produce different results even when evaluating the same materials.

Many attendees were concerned about the order of events, citing that AI detection should have been completed during the peer review phase before any conference materials were accepted. Because AI checks were completed after conference materials were already accepted, ACM had limited time to fully investigate the potential AI generation in the conference materials. Regarding the accepted submissions that had suspected fabricated research, audience members questioned whether those papers could be removed from the conference, and if not, what evidence could be gathered from authors to determine that the underlying research took place in the limited time ACM had before the launch of the conference.

The conference organizers ultimately decided which conference papers would be removed altogether, and which would require an AI disclosure statement from the authors. It was determined that for future conferences, ACM should 1) have clear guidelines for conference organizers and authors on acceptable AI use; 2) determine and disclose which AI detection tool, like Morressier, is their company’s standard; and 3) require that all AI checks be executed before any conference materials are accepted.

References and Links

- COPE Council. COPE guidelines: editing peer reviews—English. https://doi.org/10.24318/AoZQIusn.

- https://www.morressier.com/products/research-integrity-manager